Publications

Publications

Psychopolitics: Surveillance and Segregation in Facial Recognition

Algorithms and artificial intelligence Privacy and surveillance

Surveillance cameras, drones, biometrics, algorithms, or digital identities. It’s hard to conceive the ecosystem of urban services without considering an array of new integrated technologies. Among other factors, this trend is driven by the emergence of a new city management mentality focused on capturing and accumulating personal data. Within this context, facial recognition technologies have emerged under a modernizing rhetoric, bringing to light new levels of surveillance and technological insecurity for society. These technologies revive the legacy of discredited pseudosciences and questionable technical efficiency, sparking contentious political reactions worldwide..

“Recognition technologies” gained traction, like many others, after the September 11, 2001, attacks. They aimed for a new way of identifying potentially dangerous objects and suspicious behaviors in public spaces. This algorithmic evolution has taken on new directions and sophistication layers over the past two decades , progressing through object recognition, car license plates, faces, speech, gait, and even emotions. New dimensions of personal data always seem to reheat markets, the innovation ecosystem, and, consequently, governments’ surveillance potential. The human body seems to be the new frontier in this mining, in open biopolitical exploration. Facial recognition, in particular, has become a more present phenomenon, sparking essential discussions on the development of artificial intelligence and its role in making critical decisions and mediating interactions between citizens and public services.

Facial recognition extends beyond preventing terrorist actions or public security purposes. It applies to the most diverse societal life circles, ranging from personal authentication for public transport use and identity checks at airports to monitoring school attendance for children — or even gauging happiness levels at summer camps. Suddenly, algorithmic mapping of facial traits and expressions seems to be an important part of social relationships.

However, when we examine the use of facial recognition beyond the narratives of efficiency and service optimization, it clearly reveals political dimensions, as well as ethical issues concerning the companies that develop these solutions and systemic human rights violations by state agents using this technology.

Public-Private Persecutions

IBM can be placed at the center of these issues: it was documented that the New York Police Department provided surveillance camera footage to the company to develop a facial recognition system based on skin tone, which could subsequently be used for monitoring ethnic minorities. Beyond the serious concerns over the data provision from an entire community to a private company, without privacy policies or public scrutiny, establishing racial and ethnic criteria to create targets for suspects can be considered a policy of persecution disguised under a public safety agenda. Another investigation, led by Human Rights Watch, points to the supply of facial recognition technology to the Philippine public security program, led by Rodrigo Duterte, a head of state notorious for persecuting and killing political dissidents through his “death squads”. In this case, facial identification enabled by technology has been used to suppress political freedoms, reflecting a growing expression trend of government surveillance.

In another context of large-scale political monitoring — China — facial recognition is already extensively used in many locations. Specifically, in the Xinjiang region, on the Chinese border with countries like Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, the technology takes on segregationist contours, monitoring and controlling migratory flows of the Muslim population in that region, especially the Uighur community. In this way, some surveillance systems are explicitly designed to marginalize ethnic minorities, keeping them under observation from all sides: surveillance cameras, drones, biometrics, algorithms, or digital identities.

Eugenics, segregationism and algorithms

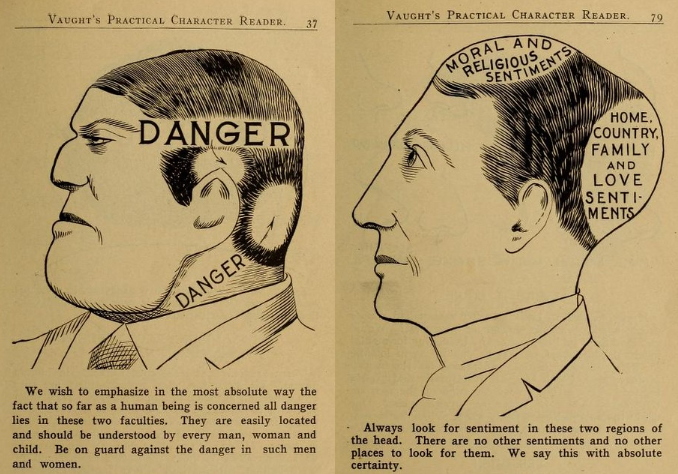

Interestingly, when we closely examine the sciences that seek to analyze physical traits and expressions — now revived by artificial intelligence — we quickly encounter branches of medicine and psychology once prominent in criminal science. This is the case with physiognomy, a proposal to identify an individual’s personality and character based on their facial topology, often associated with animals. This pseudoscience was a popular science in 19th-century racial segregation policies and during the Nazi regime. Another example is phrenology, a theory that claims to determine an individual’s mental aptitudes based on the shape of their skull. A further expression of these ideas can be found in the work of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso, famous for associating natural facial features with a propensity to commit crimes.

In 1862, Benjamin Duchenne wrote Mechanisms of Human Physiognomy. By applying electrodes to volunteer patients, the neurologist activated their facial muscles and claimed to be able to observe their facial maps. He argued that it would be possible to code nerve responses into taxonomies of internal emotional states. More recently, psychologist Paul Ekman’s theories — that emotions are fixed and can be categorized into a small set of groups, regardless of cultural or ethnic differences — have been associated with the development of technologies for algorithmic emotion recognition via facial analyzes , an update of Duchenne’s “algorithm”.

Translating the theories: the U.S. Transportation Security Agency (TSA) has been using camera algorithms to identify “suspicious facial expressions”, subjectively interpreting emotional states that might indicate a potential risk of attacks. Unsurprisingly, these profiles often align with stereotypes about Muslims.

Beyond a history — and a present — suggesting a resurgence of racist and eugenic policies, recent research highlights undeniable discriminatory tendencies in some of today’s most modern facial recognition algorithms. According to the Gender Shades study by MIT, technologies considered cutting-edge, such as those from Microsoft and Face++, show low accuracy in recognizing Black people and/or in identifying the female gender; another study, conducted by the American Civil Liberties Union, points out that Amazon’s facial recognition technology, Rekognition, misidentified twenty-eight members of the U.S. Congress (the vast majority of them black) with people wanted by the police. Once again, high-impact technologies that are not subject to broad public scrutiny can reflect structural inequalities in their architecture.

Regulations, cages and subjectivities

Tensions like these, triggered in large part by police surveillance programs, generate social, legal, and political insecurity, consequently impacting a range of regulations that seek to address public demands. The city of San Francisco, for example, has chosen to ban the use of facial recognition by government agencies in public places. In addition, the city has been discussing regulations for the use of technologies for surveillance purposes, which can only be implemented if a specific report proves that the benefits to public safety outweigh the impacts on human rights. What remains to be seen is whether Brazil will continue to implement this technology unrestrained, without prior public debate, and with broad civil society participation, remains to be seen.

The Brazilian General Data Protection Law also does not specify prior rules for using critical technologies based on biometric data in public surveillance policies. They still fall into the gap created by the exceptions in Article 4, items I and II (processing of personal data for public security and national defense purposes), which could serve as a loophole for extensive facial recognition programs. Civil society should remain vigilant about the directions that l monitoring may take, especially regarding the political and segregationist purposes these technologies may serve.

Ultimately, beyond the impact on privacy, biometric algorithms affect personality formation, limiting and trapping subjectivities and creating an “informational cage,” as Shoshana Magnet points out. Objectifying or binarizing genders, which are in constant flux and discovery, influences personal development and infringes on identity freedoms, resulting in structural violence, as facial recognition often fails to recognize non-normative elements. It is thus essential to restructure the paradigms within which technologies and biometrics developed so that they do not come with repressive designs.